If you’ve been following a low-carb or ketogenic diet for a while, then you’re steering clear of high-carbohydrate foods. But have you ever asked yourself what exactly carbohydrates are? This might seem like a silly question, but as a nutritionist, I can tell you it’s not as obvious as you might think.

So here’s a quick primer on dietary carbohydrate.

What are carbs?

When it comes to the foods we regularly consume, “carbohydrate” is an umbrella term that includes several different molecules. Some of these are structural components (like the fibers in the stems and leaves of plants), and some are stored energy (such as fruit and underground roots and tubers, like potatoes.)

All carbohydrates are made up of simple sugars, called monosaccharides. (“Mono” means one; “saccharide” means sugar.) Two monosaccharides bonded together make a disaccharide, three make a trisaccharide, and more than that make a polysaccharide.

Types of carbs

Monosaccharides: glucose, fructose, galactose

Disaccharides: sucrose (a.k.a. “table sugar” – glucose + fructose), lactose (“milk sugar” – glucose + galactose)

Trisaccharides: raffinose (glucose + fructose + galactose)

Polysaccharides: starch and fiber (both are many glucose molecules linked together)

Just about all foods have carbs

It’s important to understand that, except for things like isolated fats and oils (which are purely fat), refined sugar (which is pure carbohydrate), and egg white or whey powder (which are nearly pure protein), just about all foods are combinations of protein, fat, and carbohydrate.

One of these macronutrients predominates in each food—for example, beans are mostly carbohydrate and protein but they’re higher in carbs than protein. Nuts contain protein, fat, and carbohydrate, but fat is the predominant macronutrient.

Not all carbs are starchy

When you think of carbs, what comes to mind first? Probably things like bread, bagels, pasta, rice, and potatoes—foods that are high in starch. But starch is only one type of carbohydrate.

There’s a long list of foods that are predominantly carbohydrate but which we don’t typically think of. Lettuce, broccoli, eggplant, spinach, zucchini, strawberries, and lemons are examples of such foods.

Most of the calories in these foods come from carbohydrates–just not starchy carbohydrates. You might not be accustomed to thinking of lettuce or cabbage as carbs, but they’re clearly not fats or proteins, so there’s only one category left.

Of course many sweet foods (both natural and manmade) are sources of carbohydrate as well. Fruit, carrots, beets, tomatoes, honey, maple syrup, jams and jellies, candy, sugar-sweetened beverages, etc. It’s pretty obvious that all these high-sugar foods are carbs, but they may not be what springs to mind first if you have to name some high-carb foods.

Starch and fiber

Starch and fiber can be classified more specifically as several unique molecules with different structures.

Starch contains amylose, which is a long, linear chain of glucose molecules strung together; starch also contains amylopectin, which is built from multiple chains of glucose molecules strung together but also branching off from one another. (Click here and here to see how different amylose and amylopectin are, even though they’re both made from glucose.)

There are numerous types of fiber. They can be placed into two main categories: soluble and insoluble fiber.

Soluble fiber dissolves in water; insoluble fiber does not. Some kinds of soluble fiber form a viscous gel. Chia seeds, for example, are high in soluble fiber, which is why you can make thick puddings using chia seeds.

Soluble fiber also may lower blood cholesterol levels, although whether this is something we should all strive for is a matter of debate. (See here for a summary of cholesterol on a keto diet.)

For insoluble fiber, think of the outside of flaxseeds or broccoli stems—a tough, almost wood-like texture that’s hard to imagine dissolving in water. Because of its gelling properties, soluble fiber is often used to thicken foods and provide a creamy texture, especially when it replaces fat.

(When you see guar gum, acacia gum, or psyllium in an ingredient list on a food label, those are soluble fibers being used for that purpose. Look at the labels on reduced-fat ice cream next time you’re at the store. You’ll see some of these.)

Insoluble fiber increases stool bulk and may help relieve constipation. (This isn’t a guarantee, though: in some people with constipation, increased fiber can actually make things worse!)

What happens when you eat carbs?

The chemical structure of the different types of carbohydrates determines their metabolic effects when you eat them. Generally speaking, the more quickly you digest and absorb a carbohydrate-rich food, the larger the effect will be on your blood sugar.

Liquid sugar—fruit juice, sugar-sweetened soda—typically has a bigger and faster impact than things that contain fiber and take longer to digest. (This is why when someone with diabetes is experiencing hypoglycemia, you would give them a small shot of orange juice or a tablet of pure glucose rather than a stalk of broccoli!)

Why does the molecular structure matter?

The reason the digestive effects depend on the molecular structure of the various carbohydrates is that some of the chemical bonds cannot be broken by digestive enzymes produced in the human body. If you can’t break the bond, you can’t absorb the carbohydrate, which is why these fibers pass through your digestive tract and add to the bulk of your stool.

But just because your own digestive enzymes can’t break those bonds doesn’t mean these foods pass through you completely unchanged. The bacteria that populate your large intestine produce enzymes that do alter some of these bonds and ferment some of these fiber carbohydrates.

This fermentation results in gas and bloating, just like if you brew beer or make homemade sourdough bread—think of the gas bubbles that form via fermentation. This is why you experience bloating and flatulence after eating beans.

Beans are high in raffinose and stachyose, two types of carbohydrate that are indigestible by human enzymes but are fermented by colonic bacteria. (Other foods high in these flatulence-producing carbs are broccoli, cabbage, brussels sprouts and asparagus. That explains a lot!)

The glycemic index is misleading

The glycemic index (GI) is often used to categorize foods based on how much and how quickly they raise your blood sugar. It’s generally true that the more quickly you digest a high-carb food, and the more digestible carbohydrate it contains, the more quickly and more significantly it will raise your blood sugar.

But the glycemic index is an imperfect guide. People vary in their sensitivity even to very quickly digested foods high in simple sugars. Two people can consume the same amount of the same food or beverage but have very different blood sugar and insulin responses.

So, don’t assume that a low-GI food will have little or no effect on you. The GI is an average or aggregate of how people respond. It doesn’t take into account individual sensitivity, particularly if someone has diabetes, metabolic syndrome, or another condition related to blood sugar and insulin. While the GI is a fixed number on a chart, it says nothing about how you personally will respond to any one food item.

Why cut back on carbs?

Carbohydrates provide energy and, let’s face it, they’re delicious. So why would anyone want to cut back on high-carb foods?

If you have type 2 diabetes or prediabetes, the American Diabetes Association has said that reducing carbohydrate intake has shown “the most evidence” for improving blood sugar.

And the world’s leading researchers in this area have said that carbohydrate restriction—i.e., a low-carb or keto diet—should be the “default treatment” or “first approach” for diabetes and metabolic syndrome. Keto is also effective for weight loss and conditions far beyond diabetes, such as migraines, high blood pressure, PCOS, lipedema, non-alcoholic fatty liver, and more.

But this doesn’t mean you shouldn’t eat any carbs, ever. (Although it’s possible to follow a zero-carb diet if you want to.) If you need to control your blood sugar or you’re trying to lose weight, you can enjoy your carbs. Just stick to the ones that are low in sugar and starch.

Want to learn more? Here is an excellent and quick guide to carbohydrates from nutrition researcher Zoe Harcombe, PhD.

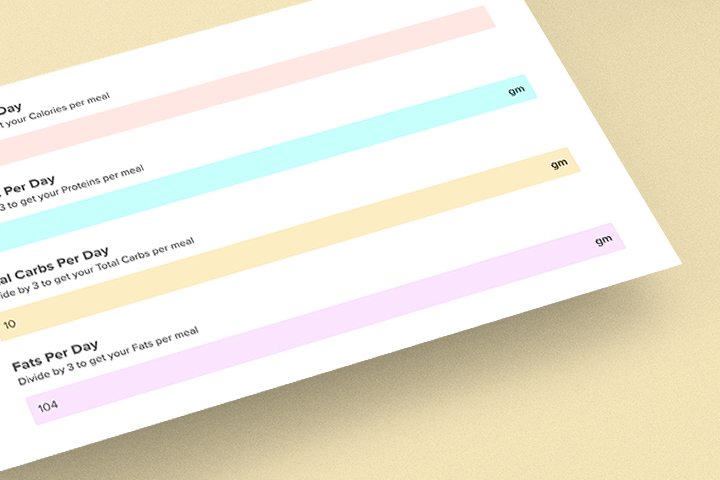

Want to make your low carb diet easy?

Then check out Keto Chow! Keto Chow is a meal replacement shake or soup base that has 1/3 of your daily recommended nutrients. You can choose from over 30 different flavors, each only taking around two minutes to prep into a meal.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

- Hours: Mon - Fri 8AM - 5PM (Mountain)

Shop

Account

Company

The content of this website is not intended for the treatment or prevention of disease, nor as a substitute for medical treatment, nor as an alternative to medical advice. Use of recommendations is at the choice and risk of the reader. If you are on any medication, please consult with your family doctor before starting any new eating plan. Keto Chow is not intended to treat, cure or prevent any disease. Pregnant or breast feeding women should consult their health care professional before consuming.